China approaches WTO watershed

By Katherine Jo

The world of trade is bracing for a December showdown that could shake up current anti-dumping practices and set the tone for global markets for the foreseeable future.

The World Trade Organization is scheduled to grant China full market economy (ME) status on December 11, according to Section 15 of the nation’s accession protocol. The promotion could scuttle punitive charges imposed on Chinese products by countries including the U.S. and call into question the basics of what constitutes fair trade.

The uncertainty stems from China’s deal for WTO entry back in 2001. Beijing then agreed to endure 15 years of being treated as a non-market economy (NME)—in which the state intervenes in pricing and resources—for anti-dumping investigation purposes. This provision expires next month. Now the debate is fixated on whether the language of the deal calls for major jurisdictions like the U.S. and EU to refrain from applying the NME methodology for calculating anti-dumping duties.

“If the U.S. and the EU begin treating China as a market economy, Chinese exports will be able to have their anti-dumping duty rates determined by their own prices and costs,” said Xiao Jin, a trade partner at King & Wood Mallesons in Beijing. “Duties imposed under the NME methodology have frequently been as high as 200% and 300%. This goes against common sense: no exporting company would dump prices at a third or a fourth of their production costs.”

The core issues precede the 2001 WTO accession. The U.S. came up with the idea of an NME—such as for the Soviet Union at the time—where production factors were controlled by the government rather than the market. It concluded that prices and costs of manufacturing in the home country should not be used for determining the fair value of a product. In China’s case, attaining full ME status isn’t likely to remove duties altogether.

“Even if the U.S. and EU recognize China as a market economy, there could still be a dumping margin,” said Zhou Yong, Beijing-based partner at JunHe. “It would just be more difficult to impose higher rates.”

Donald Trump’s surprise victory in the U.S. presidential elections may queer the pitch further, with the Republican having lashed out at China several times during his campaign. He has accused Beijing of manipulating its currency and dumping vast amounts of steel in the U.S., and has also threatened to slap a 45% tariff on Chinese exports.*

Market vs. non-market

The EU has five criteria for a country to qualify as an ME, while the U.S. has six. The factors include currency convertibility, wage rates determined by free bargaining between labor and management, foreign joint ventures or entities being fully permitted, and the degree of government control or ownership in production and resource allocation.

“It’s impossible to pinpoint any country in the world that is 100% market economy, and the determination of whether one is granted ME or NME status ultimately rests on political considerations,” said Dharmendra Choudhary, a foreign trade counsel at GDLSK in Washington, DC, who often represents Chinese exporters. The firm’s China affiliate is Jincheng, Tongda & Neal.

A typical ME methodology used for calculating dumping margins involves comparing the export price (i.e. the price at which the exported Chinese good is set in the foreign destination) and the domestic price, or the price at which the same good is sold in the PRC.

Meanwhile, calculations for non-market economy exports “simply disregard the PRC price and use the prices of the raw materials or the product sold in other countries,” said Zhou.

Take, for example, a dining table. The U.S. Department of Commerce (DOC), which calculates based on the factor of production, would ask the exporting company to report the raw material input, such as the amount of wood purchased and used, and how much skill and labor was employed. It then finds the price of that exact wood in several other markets like India and Thailand, compiles a list and multiplies the prices set at these countries to reach a constructive normal value. This is known as the surrogate value method.

The anti-dumping duty rate imposed on that Chinese table is eventually derived from this conceptual value. The hypothetical value arrived at is only the presumed fair value, an artificial construct designed to mimic market economy pricing, said Choudhary.

In an interview with CCTV America in May, he said that the U.S. rejects all cost and price data from China and applies a “very convoluted methodology that yields an unreasonably high level of anti-dumping duty.”

The EU also uses surrogate prices but, instead of asking companies to report the raw materials or labor costs, it checks the retail price of the whole product in other countries. In other words, they find the price of that same dining table in other markets. There are, however, ways for individual companies in China to suggest that their circumstances are different from the assumptions used for country-wide analysis and obtain a separate rate.

Will the U.S. and EU comply?

“At the end of the day, it’s really about how this result would impact the global trading system,” said Xiao at King & Wood Mallesons. “If the two largest economies don’t keep their trade promises, it could have a damaging effect on trust from the international community.”

The possibility of an ensuing trade dispute could bring collateral damage to other industries in these economies.

“My forecast is that there is zero chance that the U.S. Congress will pass a law that will come into effect before December 11 to change the criteria for China,” said a partner at a U.S. firm in Beijing. “Not only are the chances slim to nil that the DOC will find China to meet all six ME criteria, but there is also nothing about the current environment in Washington that would motivate any politician to suggest bending the rule to make the case for China.”

It’s a “terrible” time for people to suggest that China deserves to be an ME, he said. The nation’s overcapacity in aluminum and steel has created a surge in anti-dumping cases in Europe and the U.S., and “by any objective measure” people think China is dumping.

Just yesterday, the DOC launched two new investigations into whether Chinese steelmakers are shipping metal to the U.S. through Vietnam to avoid U.S. import tariffs.

“The very fact that the country is dealing with this very issue is that market forces have not been dictating production capacity in the first place,” said the lawyer, declining to be named as he isn’t authorized to speak publicly on such matters. “On these merits, I just don’t think it will happen.” He added that the EU will not have time either as its legislative process requires more days than left on the calendar.

A lack of progress in PRC state and industry reforms, weak intellectual property protection, frequent central bank intervention in currency and money markets, and foreign investment restrictions in a significant number of sectors show that China has some way to go before it becomes a free economy. (This Forbes article, written by Douglas Bulloch, is titled “China is not a market economy yet, let’s not kid ourselves.”) However, some argue that the WTO agreement must be followed.

“China needs to be treated like all WTO member countries,” said Matthew Yeo, a Washington, DC-based partner at Steptoe & Johnson. A failure to honor Section 15 would be “an obvious violation as the provision is very clear about the 15-year period coming to an end. China being subject to the arbitrary NME methodology for 15 years was part of the negotiation process for its WTO commitments and it was understood that that was the price of admission.”

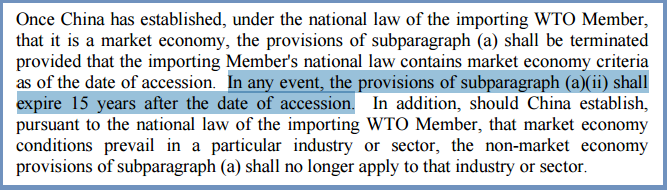

China’s WTO Accession Protocol Section 15 (d):

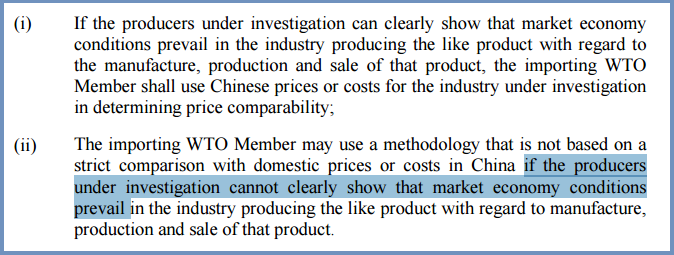

Section 15 (a):

Opinions being put forward for the U.S. continuing to treat China as an NME are totally unfounded and rely on a backwards and contorted interpretation of Section 15, said Yeo, adding that a failure to comply would be unfortunate because the U.S. is constantly criticizing China for non-compliance with WTO commitments.

“While it’s unlikely that the U.S. and EU will grant this by the December deadline, their practices will set the example for other countries,” said JunHe’s Zhou.

Several jurisdictions have already granted China ME status, such as Thailand, Pakistan and Australia. The major holdouts are currently the U.S. and EU, as well as India and Japan, which are also significant markets for China.

China achieving ME status would make imposing anti-dumping duty rates a less attractive instrument for countries that have relied on this provision to shield their industries, said Xiao. “They may need to improve their own competitiveness or try to resort to other means such as countervailing duty investigations.”

China’s countermeasures

The PRC government is expected to take action if it isn’t treated like a market economy, said Zhou.

“I don’t think any argument from the U.S. or EU will prevail at the WTO level,” he said. “China is pretty confident about winning the cases after the deadline and this is a highly important matter for its industries and trade sector.”

Nothing will change on the U.S. and EU front—the U.S. will continue doing things the way it has been, triggering China to file with the WTO that the U.S. is in breach, the Beijing-based U.S. partner said.

“An aggressive approach would be to argue that every single anti-dumping margin calculated on the basis of NME should be re-calculated. This would mean every other country needs to go back and re-evaluate their figures. Another option is to say ME methodology must be applied December 11 onwards.”

One possible scenario is where one jurisdiction moves to employ ME methodology before the other. For example, if the EU lowers the duties before the U.S. does, Chinese steel exporters will send more steel to the European market. This will create a trade diversion, leading European steelmakers to argue that they are getting disproportionally harmed because the EU yielded and the U.S. didn’t.

The bottom line is that filing the case with the WTO dispute resolution panel will take several years to work out, with all the consultations, negotiations, appeals and sanctions.

The lawyer also pointed out that China could try to retaliate in other ways, but now’s not the best time to increase concerns of U.S.-China trade relations due to significant rising protectionist sentiments in the U.S. and EU.

Pending matters

There are technical issues to be resolved, for instance how the expiry of the provision applies to ongoing investigations, specifically whether the U.S. DOC should use the ME or NME methodology.

“There are about 100 pending anti-dumping duty measures implemented as we speak, and whether all the different countries would revise their rates for these cases makes this a much more complicated legal issue,” said Xiao.

The debate comes as China scored a victory on October 19 in a WTO complaint against U.S. methods of determining anti-dumping duties on Chinese products in several industries including machinery and electronics, light industry, metals and minerals.

Specifically, the dispute panel found fault with the U.S. DOC’s zeroing practices—a controversial and somewhat criticized calculation method used by the U.S. that often results in higher margins and anti-dumping duties than the actual amount dumped–in certain cases of targeted dumping, which involves foreign importers cutting prices on goods aimed at particular regions, customer groups or time periods.

“The general opinion of the legal circle and academic experts in China and other countries is that the U.S. and EU would be in breach of the WTO agreement if they don’t grant China ME status,” said JunHe’s Zhou.

*Updated with impact of Trump’s U.S. presidential election on November 10.

Email the writer at [email protected].